Free Lessons

Myths About reharmonization

Last week, we started looking at reharmonization, and I gave you an brief overview. This week, I want to discuss a few myths that plague church pianists and introduce a first concept to start studying.

I am about to start throwing out a lot of chord names. If you need a refresher course on naming chords, please read this chord cheatsheet I just wrote before starting this lesson.

Myth 1: Reharmonization is all about chord substitutions

In the past, I have touched on why this myth is not correct. One thing I have said is that there are actually four factors that affect harmonization:

- The actual chord itself (along with all color notes).

- The voicing of the chord. (where each note in the chord is positioned on the keyboard)

- The way each individual note in the chord is played.

- The chord progression (how each chord relates the chords before and after it)

One thing you are going to learn over the coming weeks is that simply knowing a chord substitution is not enough. Often, it does not work unless it it is in the right progression and is voiced correctly.

Also, I want to emphasize that the existing chords can be made infinitely more interesting just by adding 7ths and other color notes to them. I do not actually use actual chord substitutions as much as I just modify existing chords.

Myth 2: The melody note has to exist in the triad of the chord it is used with.

In the key of C, when a C chord is written and the melody note is C, most church pianists will try to substitute either an A minor or F major chord because those are the two triads besides C major that have a C in them.

Those kinds of substitutions may work, but they are only the tip of the iceberg. For example, you could play 10 out of the 12 possible dominant chords (the exceptions are G and Db, but I will explain that later).

Besides those 10 dominant chords, you also have the possibility of using many minor 7th, major 7th, half diminished, full diminished, and various other chords. Not all of them would work in every situation–the actual choice would be largely determined by the chords around it.

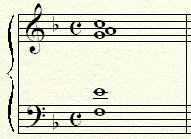

One of the things that you should know is that if you are looking for interesting harmony, you actually want to consider moving the melody note from the 3rd or 5th of the chord. It will sound more interesting. For example, I like playing minor 7th chords where the melody note is the 11th of the chord. So, I might make the following substitution from FMaj7 to Gmin7:

There is certainly nothing wrong with the first chord. The major 7 chord is beautiful, and this one has a 9th added. However, the second chord voicing gives a very unique and wonderful sound. This happens to be one of my favorite voicings.

Myth 3: Some substitutions always work.

I am not aware of any substitution that will ALWAYS work (sound good). There are a few that come close, but there always seems to be situations where they do not really work. Often, the exception arises from a melody note conflicting with the substituted chord. More often, the conflict arises from the chords around the substituted chord.

Myth 4: Most reharmonization cannot be explained–it just sounds good.

If that were true, teaching reharmonization would be practically impossible. I would have to just tell you to experiment and figure out what sounds good. The good news is that practically everything can be explained, and I will attempt to do so as I talk through these techniques. That being said, some things ARE unexplainable in the context of Western harmony (in that they may sound good even when it makes no sense), but we are probably not going to get to that level. That kind of harmony is associated with the very greatest pianists and writers alive (of which I am not one).

Homework: The first substitution – ii7 for V

NOTE: From now on, if I use lowercase roman numerals, I am referring to a minor chord. In other words, ii7 means a minor ii chord with the 7th added.

You are going to learn that one of the easiest chord substitutions is subbing a ii7 for a dominant V chord (assume any major V you see is dominant even if the 7th is not present). In the key of C, that means subbing a Dmin7 for G7. Sometimes, it means turning two beats of G7 into a beat of Dmin7 and a beat of G7.

I am going to discuss this substitution in detail over the next week or two. Today, I just want to introduce it and give you a homework assignment. Find “Trust and Obey” in your hymnal and do the following.

- Identify the V7 chord in the key it is written in.

- Circle every occurrence of the V7 chord in the hymn.

- Identify the ii7 chord in the key the hymn is written in.

- Play through the hymn and work out places where you can substitute the ii7 for the V7.

- Look for places where you can divide the beats of a V7 into half with a ii7 chord and half with the V7. (This will typically happen where the V7 chord is played for at least two beats.)

Important: Do not worry how the melody note fits into the ii7 chord. Just play the melody note in addition to the chord if you do not believe it really fits into the chord.