Free Arrangements

Analyzing "Hiding in Thee" (Part 2)

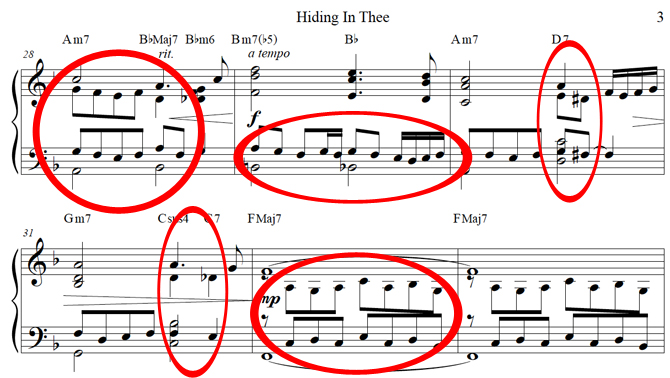

Today, I want to get into the voice leading in this arrangement of Hiding in Thee. To do that, we are going to examine just 6 bars of the song. Here they are:

First, make sure you can see the voices. This is not a highly structured baroque piece of music in which I intentionally use 2, 3, or 4 voices throughout the entire piece. At different times, you will see different numbers of voices. However, in general, there are 4. I suppose bar 32 is the best representation of that. You have the top voice which has melody, a bass voice that contains the roots of the chords and two inner voices.

Let’s start by looking at what I have circled in bar 29. That is a line written for an inner voice. Some of you might think of it as a tenor voice. Note that it steps rather than jumps. If you are going to have smooth voice leading, you will be using a lot of steps. I am actually using steps to connect starting notes and ending notes. Those starting and ending notes are defined by the chord. In this particular example, I am moving from an A in beat 1 to G in beat 3. Those notes match the chords in those beats. So what I did was write a line of steps connecting those two notes.

When connecting notes in this way, your line should ideally be smooth, interesting, and accentuating the natural voice leading that is happening.

Moving on, I want to step back to bar 28. This demonstrates something I really like to do: doubling a inner voice movement. Some might not like this; Bach might not have liked it either (though I am sure he did it sometimes). Some might say it breaks the rule of doubling that I preach a lot.

The reason you double in spots like this is to accentuate the inner voice movement. It just highlights it a bit and makes it sparkle. To me it is a way to connect with an audience a bit on a non-intellectual level. A counterpoint purist might sneer a bit at this but for normal folks, it makes things a little more accessible. It also makes the piece more accessible for the pianist trying to learn it.

I don’t know that I would write a whole song with doubled inner voice movement but I certainly use it often. You will see it a lot through this particular arrangement.

Look at bar 32. Bar 32 demonstrates parallel and contrary motion. In general, this arrangement uses parallel motion with lines moving either a sixth or third apart. That is an easy way to write and is easy to learn. But on the other hand, it is generally accepted that contrary motion is stronger. So use some of it. If you are writing for other pianists, don’t go crazy unless you are writing for advanced pianists.

And last, look at bars 30-31. This is an easy way to start getting voice leading into your music and it involves suspended dominants (some of you know this chord as a IV/V).

Very often, you can change the V7 chords in a song either to Vsus or a progression of Vsus – V7. The same is true for any other dominants (secondary dominants) you run across in a song. You cannot do it when the melody note is the third of the chord (because a sus chord does not have a third in it). If you change a V7 into the Vsus – V7 combination, the sus chord should always come first. It naturally resolves to the dominant.

A Vsus – V7 progression is a great example of voice leading because the 4 in the sus resolves beautifully to the 3 in the dominant. Look at the beats 3 and 4 in bar 31. That is a Vsus – V7 progression. Look at the inner voice in the bass clef. That is your 4 resolving to a 3. Do you see how this voice leading sort of writes itself? The important thing is that you need the 4 to resolve to 3 in the same voice. That is the way people will really hear it.

Note that I have voice leading in the inner voice in the treble clef going on at the same time. D is moving to Db. That the 9th of the chord moving to b9. If you watch my harmony, you will see that I love flat 9ths. They are beautiful, and this voice leading is a great way to incorporate them.

In bar 30, you see exactly the same thing except I did it on a secondary dominant (D7 or the V/ii). While the chord is labelled D7, it is actually a very quick Dsus – D7 progression. Again, you see 9 to b9 in the treble and 4 to 3 in the bass.

Hopefully, this will get you started on doing this. Let me give you a last piece of advice. Throw out most of the so-called rules of counterpoint. You don’t have to follow the rigid rules that Bach and his crowd set up for themselves and that you may have learned in college. The only rule you need to care about is how it sounds. If it sounds good, it is good.